by Nora Frankel, 2nd year student, MPhil Textile Conservation.

It would not be incorrect to imagine that a typical day in the conservation studio for a textile conservator involves costumes, furnishings, tapestries, and many of the every day objects throughout history that are constructed of fabric. Sometimes, however, a unique object requires attention that falls well outside of this realm. Such is the case with Pilcher’s Hawk.

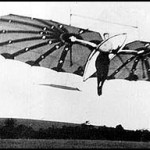

Pilcher’s Hawk is an early human-powered flying machine built by Percy Sinclair Pilcher (1862-1899) in 1895-6. Born in Bath, Pilcher spent several years in the Royal Navy before taking up an engineering apprentice with Randolph, Elder & Co on Clydeside in 1887 . During the 1890’s he was an assistant and lecturer in the Department of Naval Architecture at the University of Glasgow, where he pursued his passion for aviation becoming, by the end of the nineteenth century, arguably the country’s foremost experimenter in unpowered flight.

Pilcher’s Hawk broke the record of longest flight distance of its time. Unfortunately, although the glider was successfully flown several times, it was ultimately the cause of the inventor’s death in 1899. The Hawk, a symbol of the possibilities of science and engineering, was briefly displayed at the Crystal Palace in London, and has for many years been in the collection of the National Museums Scotland.

Due to its gradual deterioration and plans to include it in an upcoming exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland, Pilcher’s Hawk is currently undergoing conservation. The frame of the bat-like glider is made of lightweight bamboo. The wings, which span over 2.6 meters each, are constructed of canvas fabric. The mixed materials, size, and scope of the object called for a collaboration of conservators of different specialties.

Before display, the wings required cleaning. A 1961 restoration of the Hawk had replaced the original wings with new ones, and these had since become very dirty as the glider was hung suspended in a hangar. In addition to being heavily soiled, the wings had weakened areas and several tears. It became a concern for not only the appearance, but also longevity of the object.

It was decided to surface clean the wings, place them in storage, and display the Hawk with replica textiles. This decision was reached after discussing several options. Ultimately, as the wings themselves were likely from the 1960’s treatment, and not original, the issue of authenticity was less pronounced. Additionally, the proposed hanging display, which would be under a glass roof, made damage and soiling a continued issue, and without the original wings, the replicas were the only record of their pattern. Replica wings could be cleaned or discarded as needed, and a pattern could be saved in the event of any losses from the textile.

Lynn McClean, Principle Conservator: Textiles and Paper at NMS, extended an invitation to current MPhil Textile Conservation students at the University of Glasgow to assist with cleaning the wings and Harriet Perkins and I were delighted to have the the opportunity to travel to Edinburgh to be involved. We devised a work programme to ensure that the project was completed in the time available, and developed methods for handling, packing and cleaning the large and unwieldy wings that were safe for the objects but also ergonomic for us. We surface cleaned the wings using a variety of artist’s brushes and special low-suction museum vacuums. A significant amount of soiling was lifted and a great improvement was noted. While this type of treatment is not uncommon in textile conservation, it is not always as satisfying, as our work created a noticeable difference as we worked across the large object, as can be seen in the images below.

While these wings will not be on display, they are now in a safer condition and can continue to act as a record for an iconic example of British ingenuity and imagination.