By Jing Han, PhD student.

In ancient China, colour, pattern and material were all important symbols for rank, standing and for the hierarchical sequence of the society. In the court, the colour of one’s robe was, at a glance, enough to learn the grade of the royal family member or the official.

Behind this rigorous colour-coding system, there is a practical question: How were these colours achieved, and why?

In my doctoral research I dive into this mysterious world of dyeing, with the help of my supervisors, Dr Anita Quye from Textile Conservation and Prof Nick Pearce from History of Art.

Research of historical dye recipes

The starting point for my research was four historical manuscripts of the Ming and Qing Dynasties which record dye recipes. Two of them were written for general use, and two were written by experts in the field for professional use. I began by sorting out what dyes and dyeing methods were recorded. As I got further, my questions became more critical:

What specific kind/kinds of plants did the historical dye names refer to? What dyes were commonly used at that time? Why were certain dyes replaced? What is the difference between dye recipes at different times? Does the difference give a clue to how dyeing advanced during this period of time?

For some of these questions, I managed to find answers, and some I cannot answer yet. These questions lead me gradually to explore these dye recipes more and more in-depth and get unexpected and amazing results. Sometimes I feel that with certain questions research has a momentum of its own similar to a novel when the author does nothing else to develop stories but set a context and let the characters unfold.

Research on historical dyes

Manuscripts are only one side of the doctoral coin, the other side being how closely theoretical procedure is aligned with practical use.

To answer this question, I am investigating dyes of the Ming and Qing Dynasties by chemical analysis. In this aspect, I gratefully appreciate the support I have received from museums and private collectors in both the UK and China, enabling me to collect dye samples of various colour shades from provenanced costumes and textiles belonging to the imperial family and officials of different ranks.

This side of the research is even more exciting: Can I find from historic textiles tricks for dyeing not recorded in manuscripts? Can the questions not answered by literature research, such as the geographical difference in dyeing, be answered by the investigation of real materials? Did ideas of colour and dyeing interact? Again, there are so many questions in my mind.

Sampling from the back of a multi-coloured dragon badge with yellow background (early Kangxi period 1670-1680)© private collector

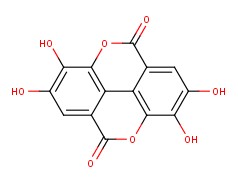

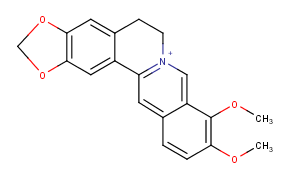

The answers are to be found within the very specific chemical structure of the dye molecule which usually contains a conjugated system formed by alternating single and multiple bonds. This conjugated system absorbs certain ranges of light therefore showing specific colours. Different dye sources contain different types of dye molecules, enabling us to predict their dye sources.

Examples of dye molecules: gallic acid (from gallnut), berberine (from Amur cork tree) and quercetin (from pagoda bud) © JH

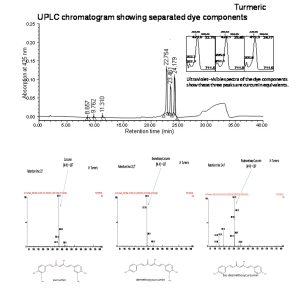

The chemical method I use is Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography with Photo Diode Array detection (UPLC-PDA) and UPLC-PDA-mass spectrometry (MS). By these methods, we are able to get much information on dyes from a very short length of thread end (approximately 0.5-1cm). In the analysis, different dye constituents are separated and identified by their retention time, UV-vis spectra and molecular ion weight. An example for differentiating the three main dye constituents of turmeric by UPLC-PDA-MS is presented below.

© JH at Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (RCE), Amsterdam

Ever since I began this doctoral research, I have been asked why I am undertaking research of a Chinese subject here in Glasgow. Well, as you see, with rigorous but free academic ambience and most supportive and kind colleagues, this is an ideal place for me to carry out this exciting research.

Papers in preparation

- Han, A. Quye. Dyes and Dyeing in the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368-1911) in China: Preliminary Evidence Based on Primary Chinese Documentary Sources. Submitted to Textile History.

- Han. Botanical Provenance Research of Historical Chinese Dye Plants. Submitted to Economic Botany.

This is definitely ground-breaking research, and I would like to read your thesis when it becomes available. Any research papers that are published in the interim would be welcome reading. All the best in your research, and well done so far!

Hi Mr. Han,

I am writing a book on Chinese rank badges from the Qing dynasty. By coincidence I saw your research on the dyes used in Ming and Qing. I saw the yellow brocade dragon roundel badge from Kangxi period. I would like to ask why you were dating this badge to 1670-1680. How come so specific? Did you use some scientific instruments for the testing? I would like to hear back from you. Thanks a lot.

Best,

Jimmy

Dear Mr Zang,

Thanks for your comment which I will also forward to Jing personally so that she is able to reply to your question directly. Sarah (blog administrator)

Fascinating. I would be interested to see how this research develops, I am intrigued by the intricacies and nuances of symbolism in Chinese textiles and costume, hadn’t realised colour was also so important. A blog update would be great!

Comment from Dr David Rosier in response to the question about dating posed by Jimmy Zang.

I will concentrate on the Kangxi Imperial Roundel illustrated in this Blog but have also included some comments which are of a general nature and equally applicable to Insignia of Rank from throughout the period.

My comments are as follows:

• Apart from a few dramatic changes as a result of the 1759 Huangchao LiQi Tushi project, changes in styles within the regulations were more insidious. Having said that though distinct changes can definitely be tracked across the period. One particularly plausible explanation is put forward by David Hugus in this book co-authored with Beverley Jackson titled ‘ Ladder to the Clouds’ and focusing on Civil and Military insignia. If you do not have a copy I would suggest this is the best work of its type.

• In considering the yellow roundel the structure and demeanour of the dragon is definitely suggestive of this period as is the extent and structure of the background design. The cloud shaping is a particularly useful tool for dating. Books by Valerie Garret and Linda Wrigglesworth touch on this topic and are useful in this respect plus Qing Court textiles in general. John Vollmer also has a number of books on the period. The older writings of Camman Schyler are also worth a read.

• The portrait dragon clearly determines this as a Qing as opposed to Ming Dynasty textile-front facing Ming Dragons were normally only seen on Festival Badges or Burial Robes for the Emperor. This example is split in the centre indicating this comes from the front centre of a Qing robe.

• The piece was apparently sourced from a Buddhist Monastery which is consistent with the soiling of the silk caused by candle smoke etc indicating this was a ‘tribute’ textile – given by the Emperor’s Court to the Llamas and Tibetan Nobles as part of a process of securing their allegiance. This process started in the Kangxi Reign.

• The outer border had been folded over and roundel stitched on to a display cloth-the border therefore has silk with its original colour and this is indicative of similar imperial yellow robes of the period.

• Looking at Insignia in general terms I find the following aspects useful:

1. The inclusion of religious or longevity etc symbols became apparent in early 1800’s under Jiajing and intensified during the remaining years of the Qing Dynasty with the exception of 1898 with the 100 day ‘Reform Period’ seeing all additional decoration removed.

2. Dragon demeanour tends to change from benign in the Kangxi to Qianlong period and a more aggressive expression as China came under pressure from Japan and Western Colonial Powers in 19th and early 20th century. A theory I would like to explore further at some point in time.

3. Aniline dyes were not available to the Imperial Workshops until early 1880’s and we see a rapid increase in their use going into the early 20th cent.

4. Shortage of silk/rapidly rising prices saw the move to more painted detail on badges in the 1820-1850 period of Kossu weave construction badges-there was a distinct shift to embroidered badges after 1850.

5. Badges with applique birds or animals represent examples from 1890’s to 1911 as does the appearance of monochrome examples.

6. Roundels with Rank Birds represent the decay in Imperial Authority and date to early 20th cent. when cash for honours and promotion became common place.

7. The use of solid gold couching ground indicates generally a group of badges from Kangxi period and was ‘reinvented’ in mid 1800’s

[…] recent decades, the dyeing of costumes in ancient times has seen growing interest. Research has been carried out based on both documentary and physical evidence – that is, dye recipes […]