by Nora Frankel, 2nd year student, MPhil Textile Conservation.

Wet cleaning of historic textiles for conservation is a surprisingly complex process. As textiles in collections can often contain degraded fibres, multiple layers and mixed materials, the practical and ethical decisions of washing increase drastically. While wet cleaning may benefit some materials, it can potentially cause damage to others, a challenge that I encountered during my second year treatment of an 1820s cap.

The cap, if something so extravagant can be called such, is owned by Glasgow Museums, and is made of net, lace, and pink silk ribbon. The structure of the cap is supported by a frame of steel stays wrapped in silk. It’s a charming piece of costume, but the passage of time had turned it yellow, dingy, and wrinkled. Furthermore, some of the iron in the steel stays had begun to rust, causing staining on the back and potential weakening in the metal. Glasgow Museums expressed a desire to potentially display the object, which would not have been possible without a cleaning treatment.

Wet cleaning would potentially benefit the cap in several ways. The discolouration of the cotton would likely be removed, which would not only offer aesthetic improvement, but also remove water-soluble degradation products that are generally acidic and can contribute to further damage to the fibres. Submersion in water would also rehydrate the fibres, improving the hand of the textile and easing out wrinkles.

Conversely, the evidence of rust in the metal made wet cleaning a potential hazard. If the metal is actively corroding, contact with water and oxygen could promote rust formation and result in breakage or flaking. During drying, the silk fabric also might wick dark solubalised rust into the surrounding satin, resulting in worse staining than before the cap was washed.

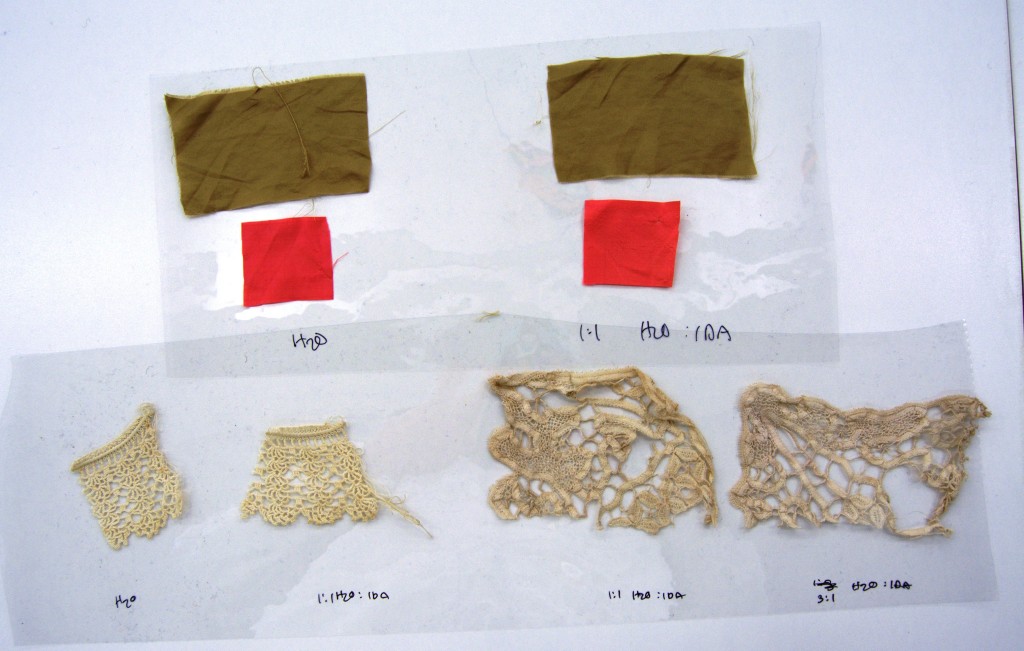

Careful consideration, research, and testing was undertaken to determine if and how wet cleaning should be conducted. Tests on a suction table showed that the lace was noticeably brighter and whiter after cleaning with a conservation grade detergent. Using the suction table for the whole treatment, working section by section was considered, but construction of the cap made it very difficult to clean the cotton adequately without wetting the metal or over-handling the cap.

After a variety of tests and research, it was decided that a short wet cleaning would be safe for the metal, and if drying time was accelerated the risk of stain transfer would be greatly reduced. After rinsing, a final bath with a proportion of industrial denatured alcohol (IDA) was used to increase the rate of evaporation. This, combined with the use of hairdryers on a no-heat setting and the aid of patient classmate Hannah Sutherland quickened drying time, and no adverse effects were observed.

In the end, the cleaning had a great positive affect on the appearance, brightening the cotton, removing soiling, and enhancing the lustre of the silk fabrics. The IDA had a temporary drying effect on the fibres, but humidification treatment restored the shape and appearance to a fuller state than before treatment. The final stages of treatment involved a few small patch supports and a storage mount, and the cap is now ready for display should it be required in an upcoming exhibition.

The increasing complexity of the objects we’ve received in our second year has helped develop many problem-solving skills that we will all continue to draw upon during our professional careers. Working on this cap has not only challenged my practical abilities, but shown me new techniques, pushed me to examine objects in new ways, and as improved my research abilities. Seeing the positive outcome was only one of the rewarding aspects of this project.

Really great project and informative for all, thanks