by Sebastian B Pin, 2nd year MPhil Textile Conservation student.

On 14th of April 1929, a Sunday evening, Martha Graham took to the stage of the Booth Theatre, New York, to present a pioneering new programme of dance which marked the debut performance of her newly formed company: Martha Graham and Group. The programme of thirteen pieces comprising of solos, trios and group choreographies brought into the public gaze a new lexicon of movement that shaped a paradigm shift for American twentieth century modern dance. Coinciding with the year of Diaghilev’s death and the disbanding of the Ballet Russe in 1929 – the forerunning cultural catalyst that revolutionised early twentieth century dance, music and stage design – Graham’s work can be considered a deeply individualistic but continuing legacy to Diaghilev’s modernist vision of deconstructing past tradition by working innovatively with the primary structure of an artform: in Graham’s case, seeking out and reinterpreting the ‘movement’ in dance. Emerging during the first two decades of the twentieth century, the early modern dance movement developed simultaneously in Europe within the schools of Rudolf Laban and Mary Wigman whose expressionistic choreography evolved from improvisation informed by movement analysis, and in America through the lyricism of artists such as Isadora Duncan and the ritualistic orientalism sought by the Denishawn school/company. Spearheaded by Ruth St Denis and Ted Shawn, the Denishawn company cultivated a second wave of American modern dance pioneers – Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman and Martha Graham – each leaving the company to develop distinctive and progressive dance techniques of their own.

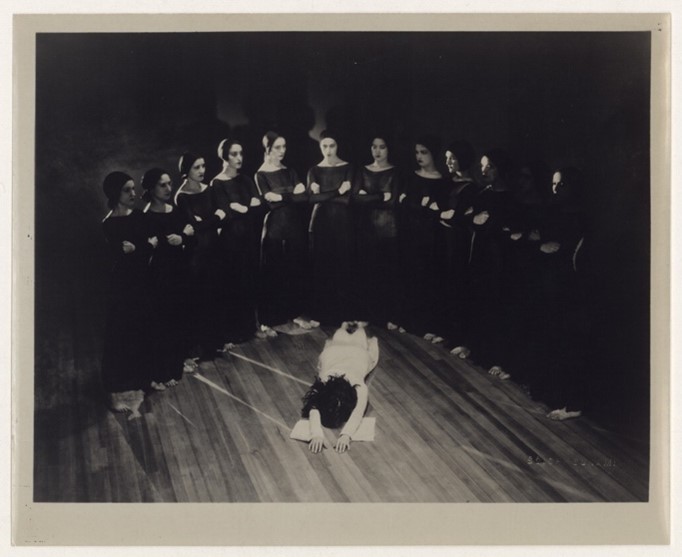

Martha Graham and Group, ‘Heretic’, 1929 – Irene Emery (likely) dancing back row, fourth from stage left. Graham, M. Heretic, No. 3. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200153372/. Reproduced with permission of Martha Graham Resources, a division of The Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, www.marthagraham.org.

By their rejection of traditional systematic ballet vocabulary, emancipation of movement from the subjugation of music and refusal to engage with gendered androcentric bias central to classical ballet, modern dance pioneers such as Graham redefined dance as an unbounded and feminist artform, one largely founded and directed by women. Working only with women dancers in early pieces such as ‘Heretic’, ‘Vision of the Apocalypse’ and ‘Moment Rustica’ as premiered at the Booth Theatre, Graham alters how the female body is traditionally viewed and used in space – rejecting passive movement typified by floating upheld positions of classical ballet for forceful movement weighted by gravity and communicated via a technique founded on the contraction and release of breath. The desexualisation of the staged female presented by Graham as an androgenous and insubordinate force, reframed the conventional portrayal of female as a sexualised being performed to maintain the heteronormative male gaze of the audience. By recentring the female body in space, Graham and her dancers opened up scope for female audience spectatorship, inviting collective female identification to the musculature and energy of the dancers’ performance not possible via Romantic ballet. [1]

This powerful artistic change manifested by the modern dance movement signified the socio-political shift reached by the late 1920’s in the wake of women’s suffrage, redefining the perception of women and their roles whilst forging new and acceptable opportunities for women to pursue paths as committed artists. The fifteen dancers forming Graham’s founding group, so devoted in expressing Graham’s vision and pivotal instruments in helping develop the signature language of Graham’s movement technique, include a 29-year-old dancer named Irene Emery.

Extracts of programme notes for the premiere performance of Martha Graham and Group, Booth Theatre, New York, 1929. (Irene Emery’s name listed as group dancer). Graham, M. & Horst, L. (1929) Martha Graham, Booth Theatre. Booth Theatre, New York. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200153348/. Reproduced with permission of Martha Graham Resources, a division of The Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, www.marthagraham.org.

When beginning to train as a textile conservator at CTC and introduced to the writings of Irene Emery by Professor Frances Lennard through her seminal 1966 publication ‘The Primary Structure of Fabrics: An Illustrated Classification’, I was not only compelled and entranced by the analytically forensic research, observation and descriptions systematically defining weave structures but felt a visceral curiosity to wonder what personality lay behind such astonishing hand and mind. Initially training as a dancer myself at Laban, London, where Graham technique was a core specialism, I was astounded when discovering the link between Irene Emery, authority on the structure of textiles and Irene Emery dancer – one so intrinsically woven into such a pioneering era of modern dance history.

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, at the turn of the twentieth century, Irene Emery (1900-1981) was descended on her mother’s side from industrialist William T Powers, whose structural development of Grand Rapids included the Powers’ Grand Opera House, opening in the 1880’s and on whose stage Anna Pavlova danced in 1915 during her repertory tour of America. There can be little doubt a fifteen-year-old Irene Emery would have attended this performance at her family theatre and been inspired to explore movement and dance further. Training at the Central School of Hygiene and Physical Education, New York, Emery remained on the East coast teaching dance in North Carolina and Ohio before undertaking the world’s first undergraduate degree programme in dance education established at the University of Wisconsin in 1926 by maverick dance teacher Margaret H’Doubler.

Anna Pavlova Theatre Bill at the Powers Opera House , 1915. [Photograph] Retrieved from Powers Theatre Playbills, https://powersbehindgr.wordpress.com/powers-theatre/powers-playbills/. Reproduced with permission of the author.

Researching the very original approach to movement education pioneered by H’Doubler at Wisconsin[2], her pedagogy (more in keeping with the Germanic methods of Wigman, Kreutzberg and Laban) focused on a somatic internalised understanding of movement expression: encouraging students to learn to use the body as a total instrument via improvisations based on scientific analysis. By enrolling on this two-year degree programme Irene Emery had seized the opportunity to gain a deep dance education and curiosity for movement she would not have had access to anywhere else in America at that time; coinciding (in 1926) with Martha Graham’s setting up of her first dance studio in New York where, though choreographically still reliant on the Denishawn style of her past, nascent experimentations of a new technique had begun. The dancer, choreographer and teacher Anna Halprin, studying on H’Doubler’s degree programme at Wisconsin in the 1930’s, describes the profound inspiration H’Doubler had on her students by promoting a philosophy of self discovery, personal insight and expressivity when seeking the true nature of movement – teaching how to recognise and express the creative impulse but transfer its application into all aspects of life[3]. This philosophy resonates deeply with the manifesto of Martha Graham who in later years expressed: “There is an energy to life, there’s an appetite for life – there is an excitement in the use of the body as a great instrument to portray the inner being and that of course is my desire and my passion and anything that will permit me to do that I selfishly use”[4].

Tracing the extraordinary life trajectory of Irene Emery, one can see how she applied this philosophy towards everything she turned her hand. Graduating from Wisconsin, Emery arrived in New York to train with Martha Graham, supporting herself teaching dance at The Chapin School (set up by feminist suffragist Maria Bowen Chapin to champion the education of girls) and is listed as sharing lodgings in Manhattan with fellow Graham dancer Kitty Reese in 1930. As a selected member of Martha Graham and Group, Emery was on the cutting edge of the modernist dance movement performing in key premieres of Graham’s pivotal early works – ‘Heretic’ widely considered a ground-breaking marker for American modern dance and the first highly acclaimed work of Graham’s repertoire[5]

Graham, M. Heretic, No. 2., left and Graham, M. Heretic, No. 1., right. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200153371/ and https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200153370/. Reproduced with permission of Martha Graham Resources, a division of The Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, www.marthagraham.org.

Graham, M. & Sunami, S. (1929) Photograph of Heretic by Soichi Sunami. Dance Magazine. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200155610/. Reproduced with permission of Martha Graham Resources, a division of The Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, www.marthagraham.org.

Emery danced in Massine’s landmark revival of Stravinsky’s ‘The Rite of Spring’ – first choreographed by Nijinsky in 1913 for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe and heralded as one of the first modernist works, the ballet was re-worked by Léonide Massine in 1920 and staged in America for the first time a decade later under the baton of Leopold Stokowski and with Martha Graham dancing the lead role of sacrificial virgin. Tragically, the Rite of Spring marked the end of Emery’s dancing career: breaking an ankle during rehearsals (an understandable outcome given the heavily accented movement), Emery persevered to dance the run of performances culminating at the Met Opera House, New York, with the ankle strapped under her costume but had caused irreversible damage to continue to dance long-term [6].

Left: Martha Graham in the Rite of Spring, 1930 Right: ‘The Rite of Spring’, 1930

As the Rite of Spring evokes a hymn to renewal, Emery continued to use her body/mind as a tool for self expression, studying sculpture at Art Institute Chicago before relocating to Santa Fe, New Mexico; a well-trodden place of inspiration for fellow modernists such as Georgia O’Keeffe and a setting Emery describes as “the most beautiful country in all the world”. Although her artistic legacy here has become ephemeral with age, aspects of Emery’s sculptural work survive at the Palace of Governors with a figurative bass relief carved within the interior courtyard, wood carvings held by the Art Museum, and archival images depict her 1937 execution of wall carvings at Carrie Tingley Hospital at Hot Springs, New Mexico.

Emery carving at Hot Springs, 1937 [photograph] Retrieved from Archives of American Art: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Archives_of_American_Art_-_Irene_Emery_-_3269.jpg

It seems cruel that for a person so imbued with kinetic articulacy, physical ailments proved a continuous interruption to new-found avenues of artistic expression: a diagnosis of myasthenia gravis (an autoimmune disorder causing muscular weakness) making work as a sculptor impossible. However, just as the essence of sculpture recalls a dancer’s perception of space, Emery adjusted her focus to textiles, a forerunning passion from her years as a dancer where experience constructing costume – handmade by Martha Graham and her group in early works – had encouraged her collecting of textiles. “I always had a passion for yarns and material” Emery told the Santa Fe New Mexican newspaper in 1944, “I would buy all sorts of materials thinking they would be wonderful for dance costumes. Then when I knew I could never do concert dancing again, I realised that I had trunks full of stuff that would never have been suitable for costumes!”[7]

Hand-made costumes made by Graham and her dancers inspired Emery’s collection of textiles. (1929)

Martha Graham. New York World, New York. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200153355/. Reproduced with permission of Martha Graham Resources, a division of The Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, www.marthagraham.org.

Initial work conveyed embroidered designs (often depicting modernist dance figures) before learning to weave in the early 1940’s saw Emery’s experience grow as a designer and weaver of upholstery, drapery, dress materials and decorative panels. Describing her penchant as a textile artist to “use orthodox technique in unorthodox manner”, Emery’s practice evokes the dualism of efforts learned as a modernist dancer (contraction versus release; force versus yield) by contrasting textures: one journalist describing “against a sheer linen background she will weave a heavy wool design. Or she will weave a hand-spun white Mexican yarn in a conventional linen lace pattern. The results are dramatic, original, provocative”[8]. In the summer of 1944, Emery accepted temporary appointment as a government weaver for the South-Western Range and Sheep Breeding Laboratory, an experimental project set up in 1935 within the forests of Fort Wingate seeking to conserve Navajo rug and blanket weaving traditions. This experience fuelled Emery’s career as a textile anthropologist and set into motion her lengthy study of textile classification when, identifying disparity in the methodology and terminology used when describing fabrics, the inception for her seminal encyclopaedia of textile structures was formed.

The enthusiasm, interest and support Emery received from both institutions and individuals during the odyssey of research, writing and preparation for her book is testament to the regard in which her knowledge, capability and vision were held. Employment in 1947 as research assistant at the newly merged Laboratory of Anthropology/Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe (whose collection promoted preservation of Southwest Native American material culture) brought financial support and resources, furthered by sponsorship from archaeologist Kenneth Chapman when made honorary Associate of the School of American Research (the associate archaeological school of the Museum of New Mexico). Receipt of a Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research grant (1951) and a Guggenheim Fellowship (1953) allowed Emery a wider scope of research by travelling extensively across the United States to access museum collections, libraries and archives – her endeavour finally coming into fruition under support of the Textile Museum, Washington DC, when appointed Research Curator of Technical Studies in 1954 [9]. Emery’s systematic classification of global textile structures eventually published in 1966, includes a concatenation of hand-woven samples constructed and photographed to both visually and textually illuminate the intrinsic nature of textiles to a wide audience. Her resulting legacy is a priceless masterwork, still very much the touchstone authority on understanding the characteristics of fabric structure today; a body of work reflecting an unparalleled vividness and determination of character, shaped by her dancer training. “The combination of dance and theatre stains one’s bones” Irene Emery mused, “[in weaving] there is a rhythm which pleases the dancer in me, and the exactitude of weaving – the limitation it imposes – somehow gives me a wonderful sense of accomplishment”[10].

I do so wish to have met her.

REFERENCES

[1] Susan Manning, Ecstasy and the Demon, (Minneapolis: First University of Minnesota Press, 2006), pp. 33–34.

[2] Janice Ross, Moving Lessons: Margaret H’Doubler and the Beginning of Dance in America, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2000), et passim.

[3] Ibid, pp. 163.

[4] “Martha Graham: Mother of Us All”, Doc on One, RTÉ, 02 January 1993, Podcast, website, 59.26: https://www.rte.ie/radio/doconone/646615-radio-documentary-martha-graham-dancer-choreographer

[5] Helen Thomas, Dance, Modernity and Culture: Explorations in the Sociology of dance, (London: Routledge, 2005), pp. 95.

[6] Mary Elizabeth King, Irene Emery Obituary 1900-1981, Cambridge University Press, American Antiquity, Volume 48, Issue 1, January 1983, pp. 80 – 82 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0002731600064118

[7] Dolores Scott (ed), “Irene Emery’s Broken Ankle Transformed Her into a Weaver”, Santa Fe New Mexican, 08 December 1944, pp. 2. Accessed online at: https://www.santafenewmexican.com/life/archives/

[8] Ibid

[9] Irene Emery, The Primary Structures of Fabrics. (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1966), pp. xvi

[10] Dolores Scott (ed), “Irene Emery’s Broken Ankle Transformed Her into a Weaver”, Santa Fe New Mexican, 08 December 1944, pp. 2. Accessed online at: https://www.santafenewmexican.com/life/archives/

I have always been a champion of Irene Emery’s book The Primary Structure of Fabrics: An Illustrated Classification’ as an essential tool for the training of textile conservators. I am thrilled to learn Emery’s back story! It is fascinating. Great research contribution, thank you Sebastian B Pin.

Very interesting!!- and how strange a parallel blue- started with dance but then turned to cloth!

Fragments of Heretic are still on YouTube !!

https://youtu.be/IgscJaDUM9w

Great post, thanks! Maurice

A brilliant unearthing of a seminal figure .

Absolutely fascinating – thankyou so much Sebastian

best wishes

Mary Brooks

Marvelous to learn so much about Irene Emerys background. Thank you.