by Aisling Macken, 2nd year student, MPhil Textile Conservation.

One of the most interesting aspects of travelling and living in a new country is experiencing the differences in culture. Being in Scotland, one of the biggest cultural differences to Canada is football culture. After living in Glasgow for a year and a half, I was finally exposed to this phenomenon, and being a conservation student, my exposure started with an object: a souvenir handkerchief commemorating the Celtic 1931 tour of the United States and Canada.

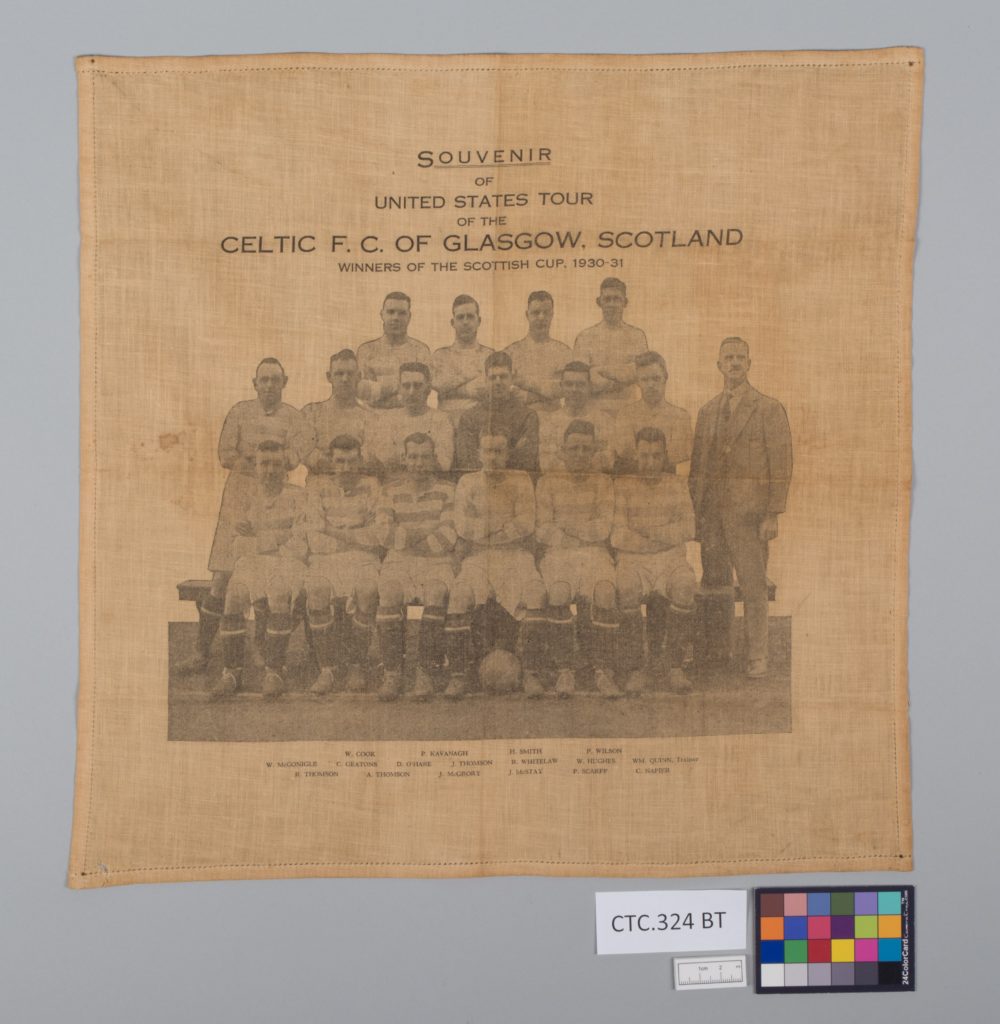

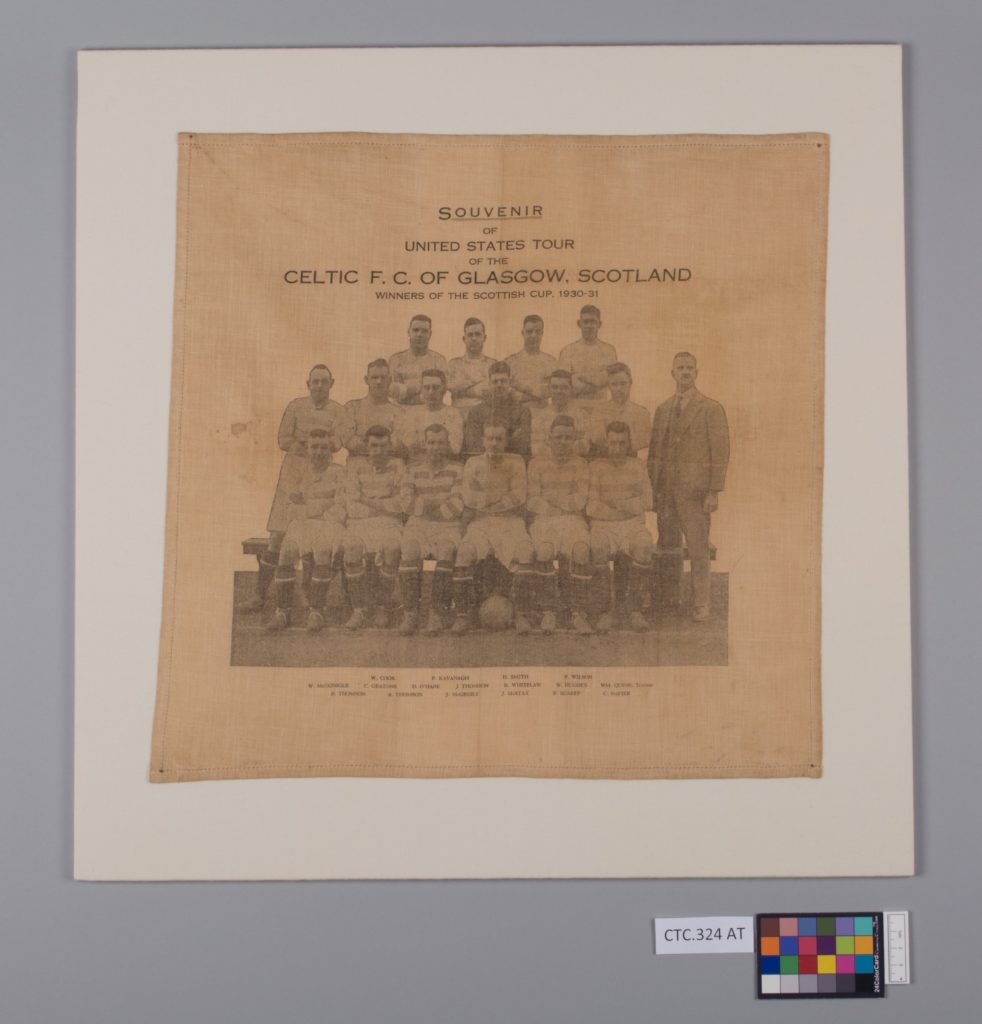

The handkerchief belongs to a private client and came to the CTC for conservation as the owner wanted the object mounted on a board and framed. The handkerchief was stained, discoloured, and creased, and I immediately knew that it would benefit from being wet cleaned. My main concern moving forward with the treatment was the printed image of the team, and whether or not I would be able to wet clean the object without damaging the printed surface.

As conservators, our main objective is to always ensure the safety of the objects that we treat, which includes plenty of research and testing before any interventive treatment is carried out. I needed to understand the potential composition of the ink used for the printing to understand how it might react in water, so I looked into possible printing techniques of the early twentieth century.

My research led me to conclude that the handkerchief was possibly printed using lithography, a process well established in the early 20th century that could quickly and cheaply produce multiples of the same image; two elements essential to the production of souvenir objects. Lithographic printing uses oil based ink, which would suggest that the handkerchief would be stable in water, however, I still undertook further interventive research.

I purchased a surrogate object, a printed commemorative handkerchief from 1936 celebrating the life of King George V. This object was similar in date and appearance to the Celtic handkerchief, and purchasing it meant that I could carry out more interventive testing than would have been ethical or safe for the actual object. I wet cleaned the surrogate object using a conservation grade detergent, and achieved very positive results; the printing ink was not affected by the water, detergent, or the mechanical action of sponging. With my hopes high, I tested the ink of the Celtic handkerchief for wash fastness.

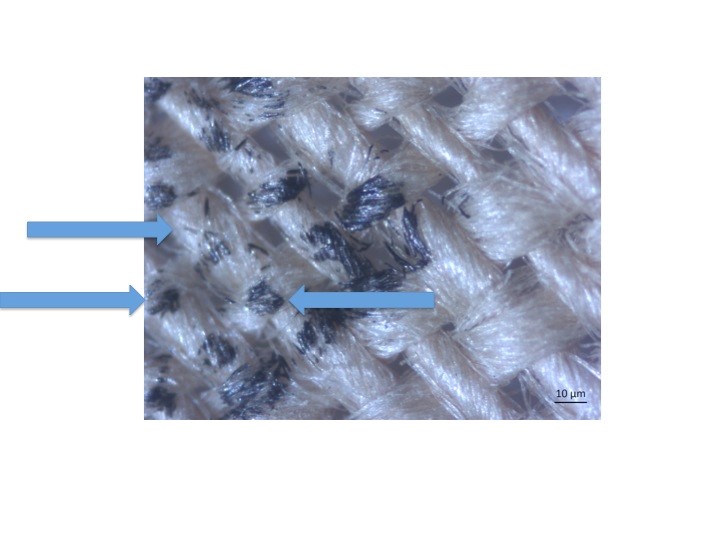

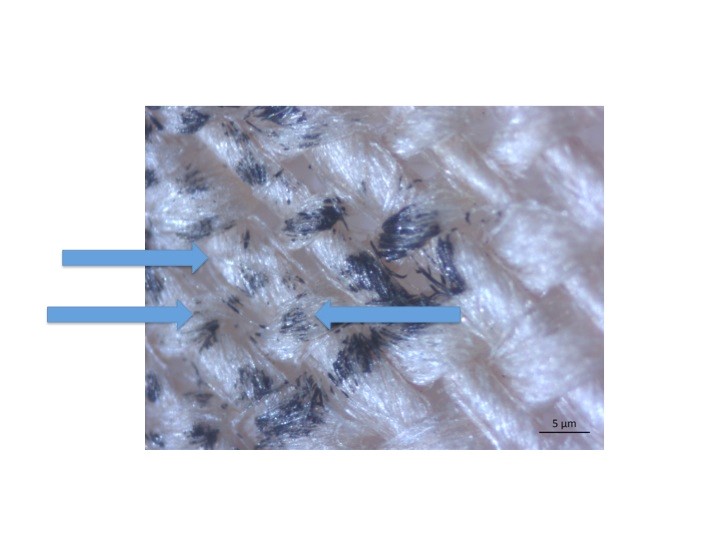

Wash fastness testing is a process that allows conservators to predict the way a textile will behave in water. I slightly dampened and blotted a small corner of the printed image, and examined the area under magnification. What I discovered was that some of the ink was removed from the blotting. The removal of part of the ink from the handkerchief was undesirable, as it is always the conservators aim to retain as much of the original material of an object as is possible, however testing for wash fastness was crucial for the overall safety of the object.

Before and after images of the area tested for wash fastness. The blue arrows indicate areas where some of the ink was remove © University of Glasgow, 2017.

Through testing I discovered that the ink was stable while wet, if no mechanical action was applied to the surface. This proved to be problematic given that textile washing techniques typically use sponges to mechanically remove the soiling from the fibres. This led me to research washing techniques in other conservation disciplines, specifically paper conservation. After researching, I decided to float wash the handkerchief. This technique floats the object on a bath of water, where the object is not handled, but the bath of water is gently agitated, and any soiling is drawn into the water below.

The treatment successfully removed the yellow discolouration, improving the overall look and stability of the object, and ensured that all of the printing ink remained undisturbed.

As conservation students, part of our task with any object is the research into the provenance of the object. This type of research can help to inform the history or the treatment to be carried out, and is a part of the project that I always find very enjoyable. I managed to find quite a lot of information on the Celtic tour in 1931, but as a Canadian I was still very curious about football culture. This research took me to Celtic Park. I had never been to a football match, and what better way to “research” the provenance of my object but to immerse myself into football life.

With three friends, we saw Celtic play Hearts from Edinburgh, and I got a first hand look at the fandom and enthusiasm surrounding football. We enjoyed the chants, shouts, fans (both home and away), pie and tea. All in all, this was one of my most memorable conservation experiences.