by Kate Clive-Powell, 2ndYear Student, MPhil Textile Conservation.

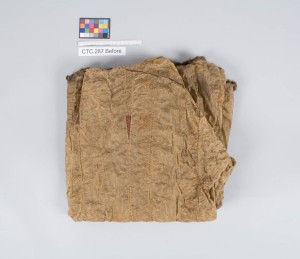

This term I was presented with the challenge of conserving an unusual object, an Inuit parka made of seal gut belonging to Glasgow Museums (Ethnn.427). A few of my course mates grimaced at the unattractive, brown crispy bundle when the parka was first taken out its box but I couldn’t have been more delighted that I’d been given it to conserve!

Last term I became fascinated by the use of gut in textiles when I researched approaches to its conservation for a literature review. Gut was principally used by Inuit people before the twentieth century to make parkas that could be worn while hunting – there are some fascinating early photographs of them being worn. The coats acted like modern day Gore-tex® jackets, water-proof but still able to let humidity out from the body. Gut is flexible when wet and brittle when dry so it is thought that oils were originally applied to parkas to keep them supple. The use of gut is currently undergoing a revival as a cultural practice, with workshops about its processing, sewing and conservation being held, in museums such as the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, USA.

The parka I was given to treat is made from seal gut. The process of preparing the gut involved washing out the intestine and scraping off the fat so that a tough sheet of muscle was left. This was inflated, dried and then cut into strips. These strips were sewn together using sinew to create the garment. Sinew was used as it swells when it is exposed to moisture which ensured that the parka’s seams remained water tight. Although Glasgow Museums had no provenance for this item the way the strips have been sewn together indicated to me that it probably came from Northern Canada, Alaska or Greenland as it was only in these regions strips of gut were sewn vertically, rather than horizontally to construct parkas.

The garment was in poor condition. The gut skin had become so brittle that opening it up from its folded state would have caused severe splitting and tearing. Because of this the museum had no record of its overall construction. Therefore my main priority was to humidify the parka so that the worst of its distortion could be removed.

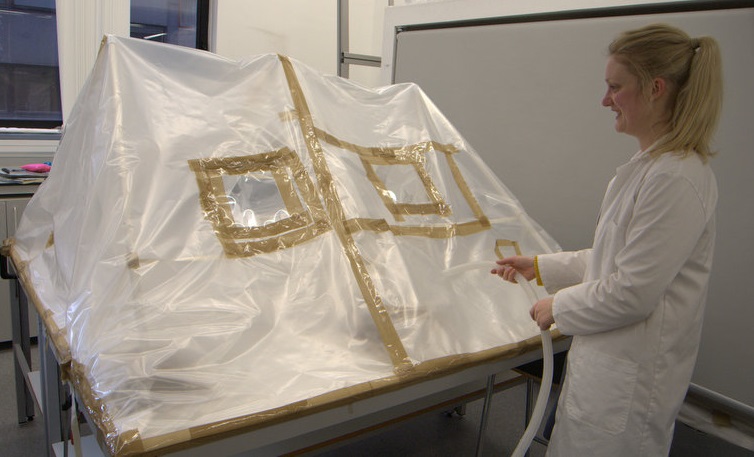

I spent a day constructing a rather large tent, which even had windows so I could keep an eye on what was going on during humidification.

The treatment was quite long, lasting five days, and was done at a high relative humidity level of 80%. This was necessary as the extreme brittleness of the gut meant that it needed to be exposed to high levels of moisture for a prolonged period before it was supple enough to re-shape.

The re-shaping process took some perseverance as the gut skin remained somewhat brittle during humidification. It had to be opened in gradual stages. I spent quite a few hours crouched in the tent gradually padding out the parka with Reemay®, a random spun-bonded polyester material.

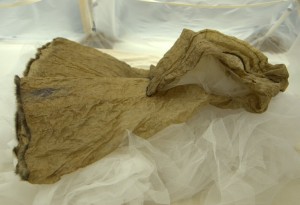

Gradually opening the parka during humidification and re-shaping the parka with Reemay®©CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection and University of Glasgow.

Reemay® was chosen because it is very soft and so wouldn’t catch on the gut skin but it still had to be inserted painstakingly slowly. Nevertheless, the result of humidification treatment was extremely rewarding as the appearance of the parka has been transformed and its construction can now be studied.

I’ve constructed a giant box to store the parka in its opened out state,and am working on a set of internal mounts to support the parka in the box. And I’m still in the process of working out how it can be most safely fitted through the door on its return journey to Glasgow Museum…..