By Yufei Xiang, Catherine Harris, Beth Gillions, Anna Robinson, Callie Jerman, Ásgrímur Einarsson and Signe Marie Thøgersen

This year placements were undertaken remotely with students working with their placement host and mentor on a project of interest and relevance to the institution. In this blog, the now second year students give an overview of their projects. As you will read they are a fascinating range which demonstrate so well both the diversity of the profession, its commitment to making advances in practice and its support for emerging conservators. Both staff and students are immensely grateful to the hosts for sharing their knowledge, expertise, enthusiasm and guidance during what was a challenging time for everyone. The feature image shows the students presenting their projects to CTC staff and students, the TCF and, for the first time and by making a virtue of the virtual, placement hosts.

Yufei Xiang, British Library

Led by senior the textile conservator Liz Rose, textile conservation intern Emma Smith and two paper conservators, from the British Library, my virtual project was to test and propose a possible treatment to stabilise a Burmese painted linen map. As it was not possible to work with the object directly, a series of tests were conducted off site which were designed to explore the possibilities of applying ‘blotter washing’ technique to the object.

The aim of the project was to stabilise the map, reduce the smell of rodent urine, minimize staining as well as consolidate the paint where appropriate and support the areas of loss. A proposal was made to test blotter washing as a cleaning method for the map based on a methodology designed by Liz Rose, which was modified from a commonly used technique in paper conservation.

The results suggested that blotter wash can an effective method to clean objects with soluble soil. However, other aspects should be considered before applying localised blotter washing test such as; dampness, paint sensitivity, soil composition, object size and dimension which affect the application setup, logistics, costs and potential risks including tidelines, uneven cleaning effect, alteration of the surface texture and potential colour bleed.

Catherine Harris, Zenzie Tinker Conservation Ltd

My virtual placement was with Zenzie Tinker Conservation Ltd, an independent conservation studio based in Brighton, United Kingdom.

Based on earlier tests done by ZTC Ltd, the project was to produce a testable method of using clay poultices and regenerated cellulose membranes (CP&RCM) to clean delicate historic textiles which are subject to dye bleed. The aim of my project was to develop the technique further in collaboration with Rachel Rhodes, a freelance textile conservator for ZTC Ltd.

The objectives of the project were:

- To produce a literature review evaluating the use of clay poultices in textile conservation and if relevant other areas of conservation where poultices are used.

- Conduct a survey of clay poultice use and results.

- Conduct practical tests using clay poultices.

- Produce a plan for a larger scale trail.

We were successful in drawing up a testable method that was based on the project objectives above that I hope to be able to develop in the future. Personally and professionally, I gained a huge amount of confidence in my knowledge and ability to advance conservation practices using scientific research. The collaborative nature of the project was very rewarding and gave me a better insight into working as textile conservator professionally.

Beth Gillions, Museum of London

My placement project was carried out in

conjunction with the Museum of London, a social history museum in the heart of

The City of London which celebrates and reveals the life of London and its

people over the last 2,000 years.

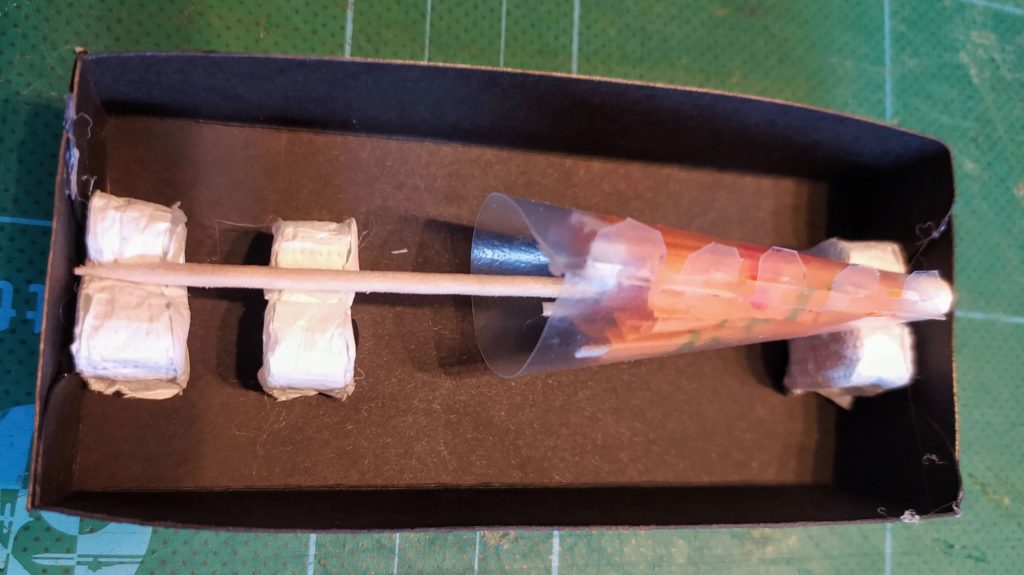

The project focussed on the museum’s parasol collection which contains 164

objects from different times, places and made of a range of different

materials. The brief was to consider the current storage system employed to

house the collection and establish if improvements or developments could be

made.

I was able to gain input and perspective from a range of people housing similar

collections in order to develop a proposal which was informed by cross

disciplinary research to create a practical and adaptable solution.

My aim was to create a storage system which fully meets the needs of individual

objects but can be applied universally across the collection to bring the whole

collection back into one easily accessible collection. I am pleased with the

layered approach to object support and storage developed, and look forward to

any opportunities to and apply the ideas to real objects and materials in the

future.

Anna Robinson, National Museums Scotland

My placement was hosted by National Museums Scotland (NMS) who gave me the opportunity to develop my knowledge and understanding of costume mounting through a project to determine the mounting requirements for 88 pieces of 18th and 19th century menswear for a proposed photography projec My research focused both on examining appropriate and sustainable methods and materials for temporarily mounting costumes for photography; and understanding how to analyse and create a historically accurate shape for a mannequin. As part of this I designed a prototype for adaptable mannequin pads, similar to sports padding, which can be used to create historic silhouettes.

Image credit: Man’s coat of brown and blue silk from around 1740, part of the menswear collection for this project. From the collection of National Museums Scotland (museum reference K.2004.88). Image courtesy of National Museums Scotland. Accessed June 23, 2020.

Callie Jerman, Philadelphia Museum of Art

I did my virtual placement with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Sara Reiter, a senior conservator there, asked me if I could look into issues with the surfactants they were using for wet cleaning and recommend some replacements. She specifically wanted to know about any environmental issues with the surfactants that are used in conservation, since we have had issues before as a community with using chemicals that work really well for us but are later banned.

Doing long-distance research from my parent’s living room was definitely a little weird, and I missed the opportunity to be in the lab and see what they do in a working conservation studio! It was also pretty isolating to be working alone, outside of a professional context, and without the reference of having my course mates around to talk things over. The flexible schedule was definitely a benefit, and I was able to keep myself to all my deadlines. I also learned about things I would have never expected, especially different methods of wastewater treatment.

On the whole I’m really happy with the report I was able to produce, and even more importantly I hope it will be useful to other conservators. Sara suggested I submit it for publication, so I have sent an abstract off to AIC to present at the Textile Specialty Group at next year’s national meeting! The idea of standing up in front of a bunch of professionals to give a presentation on my research is a bit intimidating, but I’m glad the information is getting out there and we’re working on restarting a conversation about surfactant choice.

Ásgrímur Einarsson, National Maritime Museum

During my virtual summer placement, I was fortunate enough to work with Nichola Yates and Aisling Macken in the conservation department at the National Maritime Museum.

In my project I endeavoured to answer three main questions: What chemicals had been used historically to treat museum objects? How pesticide residues can be detected and removed from objects? And what hazards to staff and visitors these pesticide residues constitute today?

In my review of the professional literature it became clear that the history of pesticide use in museum is well documented and the chemicals and their properties are known. It is still important for institutions to do independent research into their own records to determine likely hazards in their collections.

Detecting trace amounts of pesticides demands scientific methods. Heritage scientists have used handheld X-ray fluorescence (HH-XRF) devices to detect inorganic pesticides. For detecting organic pesticides, samples have to be collected by swabbing the surface of the object with a solvent or collecting gaseous traces from the air around the object onto absorbent material. The chemical analysis is usually performed by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

The examination of the literature on the effects of pesticide residues on objects and human health revealed that little research has been conducted into both topics within the heritage sector. Pesticide residues is an invisible hazard that touches conservators more directly than other museum professionals, which means we have to extra vigilant to safeguard our own health.

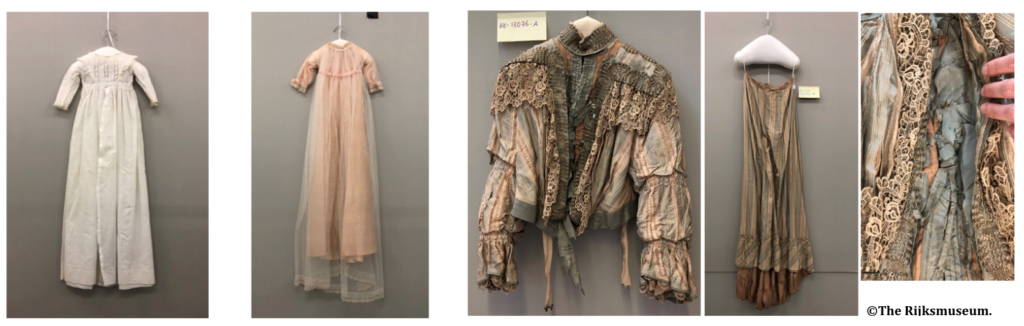

Signe Marie Thøgersen, The Rijksmuseum, The National Museum of The Netherlands.

My virtual placement was in cooperation with the textile conservation department at The Rijksmuseum, The National Museum of The Netherlands.

Having an estimated 4000 costumes in their collection but none on active display, the best way of making the costume collection available to the public are via the museum’s online gallery, “RijksStudio”.

My job was to make recommendations for the photography mounting of specific aspects of the costume collection – c. 125 very fragile pieces of 18th-19th century silk costumes, as well as c. 250 christening gowns. The mounting solutions had to be adaptable to many different silhouettes and sizes of costumes, smooth and lightweight in order to prevent damage to the fragile silks, as well as fast to make and mount.

A total of four recommendations where made taking inspiration from different fields of conservation: padded hangers with adjustable padding or a mannequin with a loose slip-cover, adjustable padding for the christening gowns, and flat mounting of the silk costumes with sectional Plaztazote® shells or soft mounts for additional padding and support.

It was very challenging working from home in Denmark, without access to materials and practical testing of the recommendations. However, the online professional community with my placement mentor, academic supervisor and peers at the textile conservation programme helped me push forward, understand the importance of preventive conservation and its effect on the individual objects. Most importantly, I have gained confidence as an emerging professional textile conservator, and I am looking forward to working with cultural heritage – both hands-on and virtually.