by Anna F Robinson, First-year student, MPhil Textile Conservation

Historic portraiture and art provide a unique and dynamic visual way for conservators to look at, understand, and contextualize how historic costume was worn and looked. Analysing period artwork for shape, style, drape and distribution of weight, was a valuable tool in a recent mounting project undertaken at National Museums Scotland (NMS) by textile conservation student Anna F Robinson.

Over the summer between first and second years of study, students on the MPhil Textile Conservation programme at the University of Glasgow undergo a work placement at a museum or private conservation studio to gain wider practical experience in the field; during their placements, students often undertake a project. I chose to do my placement with the Textile Conservation team at the National Museums Scotland (NMS). Work placements for the 2019/2020 school year were undertaken virtually due to COVID-19 related closures and restrictions.

As part of my virtual placement at NMS, I worked on a project to determine the mounting requirements for the photography of 88 pieces of menswear dating from 1700 to 1900. This period in men’s dress history is very interesting as it shows a considerable amount of change in style and design; perhaps most notably the shift from heavily decorated and flamboyantly cut long waistcoats and jackets of the 18th century through the curve flaunting, short fronted coats and waistcoats of the Regency period to the more angular and straight lined silhouettes of late 19th century suits. Additionally, the menswear collection at NMS is particularly interesting because many of the garments can be directly linked to specific people and families which played important roles in Scotland’s history, such as the brown and blue men’s coat shown here (Figure 1), which belonged to the Earls of Balcarres.

An important part of mounting historic costumes is creating supports that show the shapes and silhouettes of the garments as they were worn, so determining what the silhouettes of menswear looked like in the 18th and 19th centuries became a major focus of my research. As I was attempting to deconstruct the visual appearance and shapes of clothing, I determine this was easiest to do through research into visual media. While both modern and historic written descriptions of the design and fit of clothing exist, it is easiest to get a sense of what these shapes looked like through visual representations: because as John Berger said, “seeing comes before words”.

Paintings and other artworks are valuable, though often overlooked, historic records that have been used to look at changes and developments over human history, not only for material cultures and object history, but also in agriculture, medicine, and climate. So, I began gathering images of historic art works, particularly portraiture and fashion illustrations, from online museum collections, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Metropolitan Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. I then compiled the images into a visual library as a way of examining how the garments sat on the body when worn (Figures 2 and 3) and how the shapes and styles of clothing changed over time.

Figure 2: Man’s silk brocade coat c. 1740-1750, from the collection of National Museums Scotland (museum reference K.2004.87.1) pictured on storage hanger. Image courtesy of National Museums Scotland, used with permission.

Figure 3: Historic dummy board depicting the wearing of a coat similar to the one in Figure 2. Young Man with Sword, dummy board, oil on pine, c. 1745, unknown maker, Victoria and Albert Museum collection; museum reference W.41-1925. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed June 23, 2020.

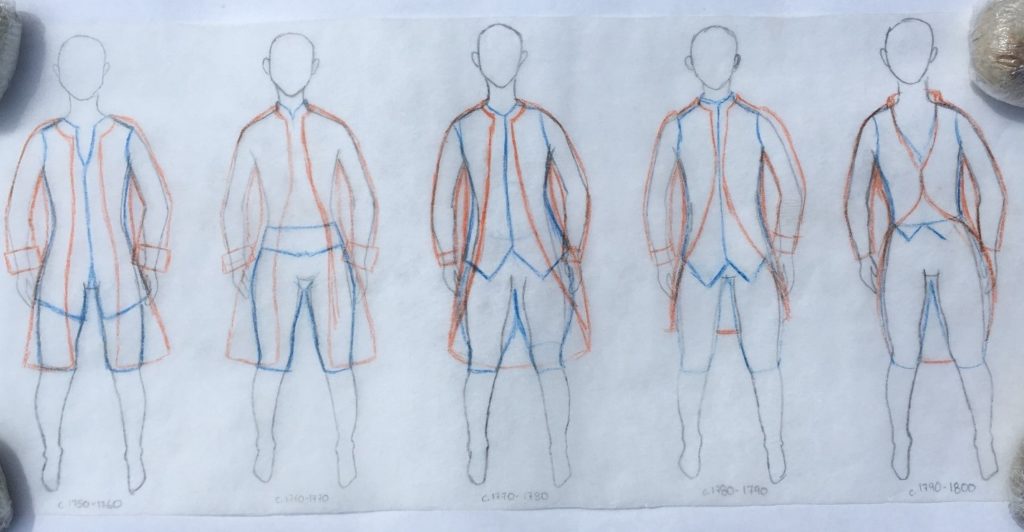

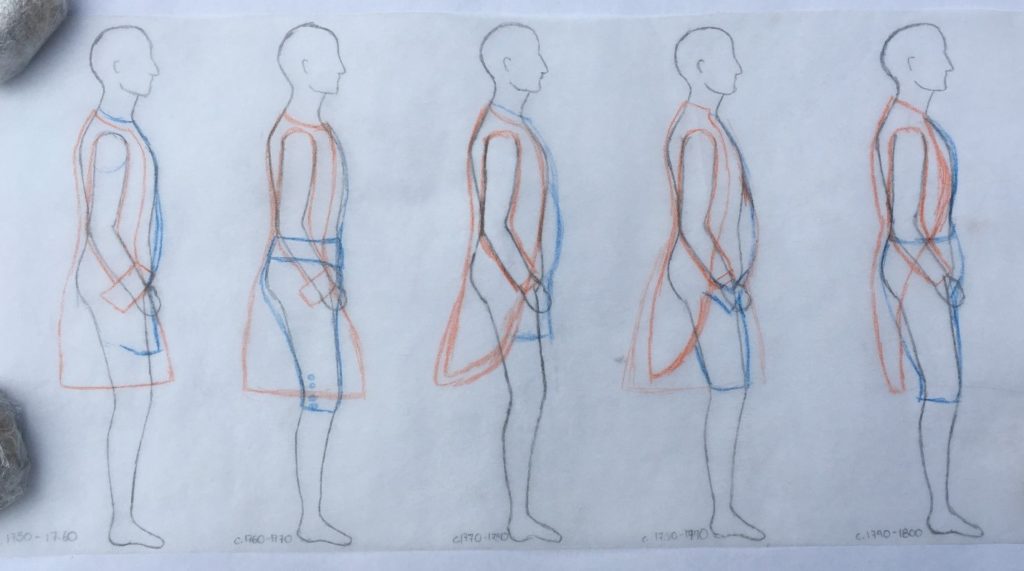

Using this image library, I created a timeline of menswear silhouettes from 1700 to 1900 by decade, cataloging the general shapes and styles of clothing both in frontal and profile views (Figures 4 and 5). From these sketches I was able to establish three key silhouettes to use as the basis for mounting the collection: a rotund, barrel chested shape for the early to mid 18th century; a curvy hourglass shape for the late 18th and early 19th century; and a boxy shape for the mid to late 19th century. These silhouettes were translated into adjustable Fosshape® torso pads, which can be strapped onto a mannequin, similar to how sports padding is worn, to create the appropriate shapes and supports to mount the garments for photography.

References

“Period Catalogues,” National Portrait Gallery. Accessed June 14, 2020. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/collection-catalogues

“Search Our Collection,” National Museums Scotland. Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/search-our-collections/

“Search the Collection,” Victoria and Albert Museum. 2017. Accessed June 14, 2020. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/

“The Met Collection,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2020. Accessed June 14, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection

Allison Meier, “The Evolution of the Watermelon, Captured in Still Lifes,” Hyperallergic, July 30, 2015, Accessed June 14, 2020. https://hyperallergic.com/226096/the-evolution-of-the-watermelon-captured-in-still-lifes/

Diego Arguedas Ortiz, “The Climate Change Clues Hidden in Art History,” BBC, May 28, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200528-the-climate-change-clues-hidden-in-art-history

Jason Daley, “Doctors Diagnose Diseases of Subjects in Two Famous Paintings,” Smithsonian Magazine, May 26, 2016. Accessed June 14, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/doctor-will-frame-you-now-mds-diagnose-diseases-two-famous-paintings-180959227/

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: Penguin Books, 2008), 7.

Larsdatter, Accessed June 14, 2020. http://www.larsdatter.com