By Dr Anita Quye, Senior Lecturer in Conservation Science.

It has been an exciting five years for my research team and I while establishing scientific dye analysis for textile conservation and dress history at the University of Glasgow, and seems hardly any time since bringing my passion and expertise for analytical heritage science to the Centre for Textile Conservation and Technical Art History (CTCTAH) at its inception in 2010. The first PhD projects started in 2012, and with the recent doctoral successes of Jing Han and Julie Wertz, the start of Mohammad Shahid’s EU Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action Fellowship, and my short research sabbatical at the end of 2016, it is a good moment to reflect on our research projects, outcomes and ethos.

Natural and synthetic dyes are coloured, often complex, chemical mixtures, so we use micro-chemical analysis by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography with photodiode array detection (UHPLC-PDA) to separate and identify them by their characteristic chromophoric compounds. Analytical profiling of known dyes enables unknown dyes to be identified by qualitative and quantitative comparison of their chemical components, and also for chemical changes from use, ageing and degradation to be investigated.

For successful and meaningful research, it is essential that we use dye references with the correct botanical origin or historically-relevant synthesis for reliable comparative chemical profiles. Our reference dyestuffs and dyed material are sourced through worldwide contacts with botanical, scientific and industrial collections and technical archives, and our literature searches take us into an eclectic world of organic chemistry, botany, photochemistry, history of science and technology, and technical analytical methodologies. Often structural analysis by mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is necessary to characterise and identify obscure components in now-obsolete historical dyes.

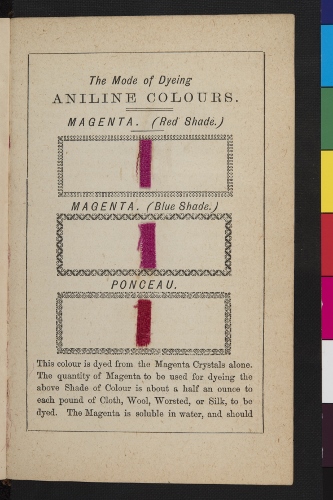

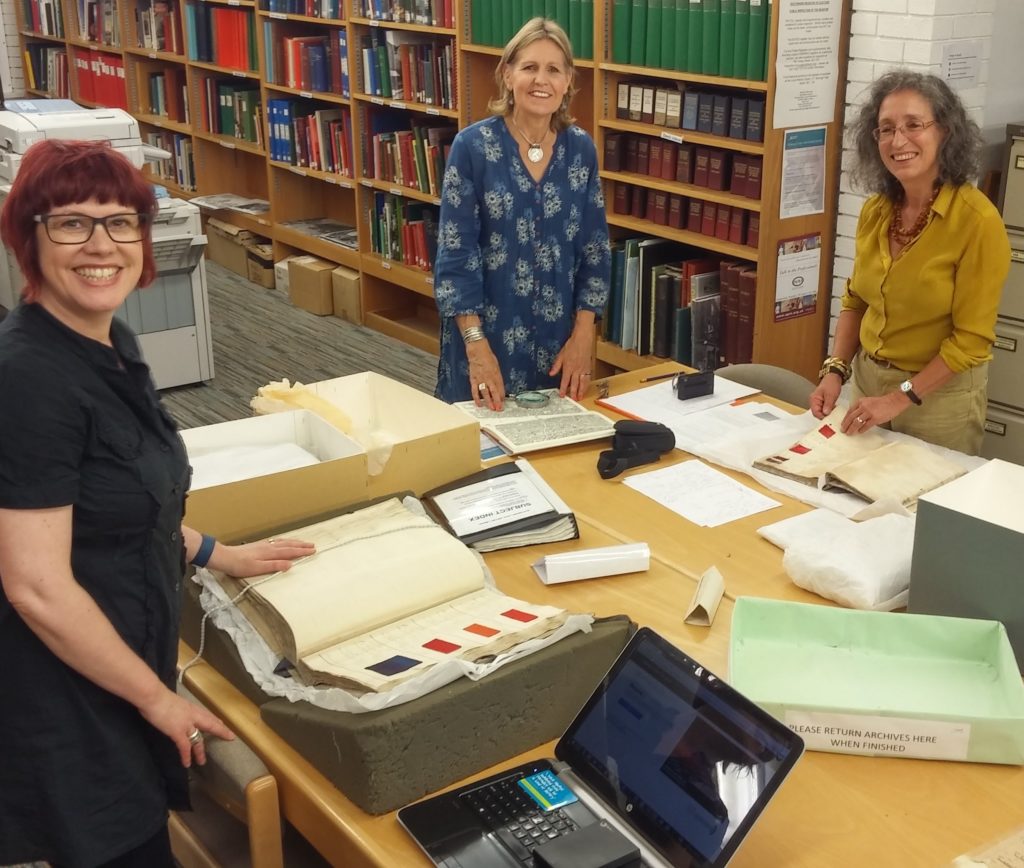

We have used our UHPLC-PDA methodology to study an interesting and varied range of historical dyes through chemical analysis combined with historical, mainly archival, research. Jing’s doctoral project revealed that high-status Ming and Qing textiles were traditionally and almost exclusively coloured with dyes like safflower, amur cork tree and pagoda bud, while Julie’s doctoral research investigated the chemical complexity of the nineteenth century Turkey red dyeing process through trends in the industrial use of natural madder, synthetic alizarin and oils for its authentication on textiles. Shahid is continuing the Turkey red textiles research with LightFasTR, a photochemical and dye chemistry study of the colourant made with madder, and my Dye-versity project is underway to understand the material properties of the early synthetic triarylmethane dyes – magenta, aniline violets and aniline blues – through named dyes in the textile ‘patterns’ and chemical information of Victorian dyeing manuals.

For our studies it is just as important and essential to interpret our scientific findings through object provenances and the technical processes of historical dye manufacture and dyeing as it is to elucidate a photo-degradation pathway or molecular structure. The identification and understanding of historical dyes brings insight in many ways: their range and availability; choices based on fastness; relationship to quality, use, date or culture of a textile; skill of the dyer; and the status of the textile’s user or owner. We aim for our research to be accessible and useful for object interpretation and documentation which informs historical significance and the decisions for display and treatment.

Outcomes from our research have also stimulated new questions, especially for the Chinese and early synthetic dyes which are light-sensitive and prone to fading. A collaborative pilot study by Jing and I has revealed that visible light from museum and archive lighting sources affects the colour and chemistry of light-sensitive natural and synthetic dyes more than is predicted from the lighting models used in preventive conservation. Most change is induced by the visible wavelengths that actually stimulate colour in the dyes. This has implications for the lighting of dyed patterns in dyeing manuals and pattern books, which are gaining significance and awareness in archive and library collections because of our research, but their increased access for study and display puts the well-preserved colours at risk of loss from light exposure. We are planning more in-depth research to improve the prediction model for selecting lighting sources for light-sensitive dyes.

Dye analysis is a powerful investigative method, but it is also specialised, costly and sample-destructive. As ethical heritage scientists, we wish to see our results being used to explain micro-fading behaviour, spectrophotometric measurements and visual observations, which are all non-invasive and more accessible to most conservators and collection managers. When dye analysis is necessary, it should be purposeful, necessary and set out to answer well-formed questions for conservation and preservation. This makes understanding and sharing the limitations and potential of the methodology an ethical consideration too, and this is the ethos for how dye analysis is included in our teaching for the CTCTAH programmes.

You can find out more about our dyes research through the publications in the links below, and we welcome questions and comments as well as enquiries for studying with us. Stay tuned for forthcoming news from Shahid about whether Turkey red made with madder is as light-fastness as the makers claimed, and my collaborative research with Dominique Cardon and Jenny Balfour Paul into the significance and sustainable collection management of a unique early eighteenth century archive from a London family of dyers…

We thank all our collaborators and supporters, and gratefully acknowledge funding from The Textile Conservation Foundation, Worshipful Company of Dyers, University of Glasgow Lord Kelvin-Adam Smith doctoral scheme, The Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, EU Horizon2020 and the Royal Society of Edinburgh-The Scottish Government for equipment, scholarships, and research initiation funding.

Anita’s web page: http://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/cca/staff/anitaquye

Jing’s publications on Chinese natural dyes http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/view/author/36834.html

Julie’s publications on Turkey red dyeing http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/view/author/37591.html

Shahid’s web page: http://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/cca/staff/mohammadshahid/#/

Jing’s PhD thesis ‘The historical and chemical investigation of dyes in high status Chinese costume and textiles of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368-1911)’ http://theses.gla.ac.uk/view/creators/Han=3AJing=3A=3A.html

Julie’s PhD thesis ‘Turkey red dyeing in late-19th century Glasgow: Interpreting the historical process through re-creation and chemical analysis for heritage research and conservation’ will be available through http://theses.gla.ac.uk/

Dye-versity project: https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/cca/research/arthistoryresearch/projectsandnetworks/dye-versity/#d.en.514388

Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/uofglibrary/sets/72157684526474115

Dye-versity UoG ASC Blog: https://universityofglasgowlibrary.wordpress.com/2017/06/08/dye-versity-for-international-archives-day/

Filtered Light Project blog: http://textileconservation.academicblogs.co.uk/filtered-light-on-light-sensitive-dyes-a-pilot-project/

Fabulous research. I hope to see so much more. Will there be plenty of publications? Such needed knowledge in understanding the rise of synthetic materials in the 20th century.