by Emily Austin, Second year student, MPhil Textile Conservation.

The second term of the final year is our chance to apply everything we have learnt so far on the course, whether that may be through documentation, choosing a suitable cleaning method, stitching or adhesive treatments. It is also a chance to gain confidence in decision making and project management.

I was very excited to find that my main project was a printed silk Schiaparelli dress c.1937 from Manchester City Galleries. I have a particular interest in clothing design which I was first able to explore on my undergraduate degree in Costume Design at Edinburgh College of Art. I am especially interested in the cut and construction of garments and how conservation treatments and mounting should be sympathetic to this.

Museum image before conservation. ©Manchester City Galleries.

In this case, the dress is required to be stabilised for an upcoming exhibition showcasing Schiaparelli’s designs at the Gallery of Costume, one of Manchester City Galleries. However, severe structural damage to the straps and large splits to the bias cut panels mean that in its current condition it cannot be displayed on a mannequin without causing considerable damage.

One of the most interesting parts of this project has been investigating the different materials and history of the dress. This has really helped me to understand the context of the object and also the possible causes of deterioration.

After initial observations and due to the date of the dress, it was clear that there may be some early synthetic components which could impact on any treatment options. I started by investigating the main crepe fabric of the dress using cross section microscopy and FTIR (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy) analysis which ruled out viscose rayon and confirmed that the fabric was silk.

Splits in the silk crepe before conservation. Magnified image of crepe weave

Images©Copyright of the University of Glasgow and courtesy of Manchester City Galleries.

The most significant areas of damage are on the straps and the back of the skirt, indicating this was mainly a result of wear. There are also inherent weaknesses found within the weave, with the weft yarns tightly spun and much thicker than the looser warp yarns as can be seen in the magnified image of the weave above. This creates tensions within the weave meaning that over time the dress could continue to split in vulnerable areas.

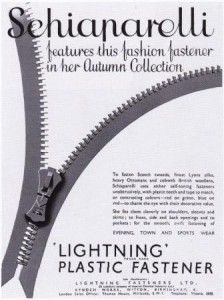

Another interesting feature of the dress is the clear plastic zip running down the left side seam. It is likely to be made from Cellulose Nitrate or Celluloid, an early semi-synthetic plastic. Schiaparelli was known at the peak of her popularity in the 1930’s for using new or unusual materials and making them a feature of her work. Now only visible under magnification is the branding ‘Lightning’ across the zips slider seen in the image below. This brand manufactured zips in Britain during the early 20th Century and was linked to Schiaparelli’s fashion house, as seen in this 1935 advert. Unfortunately degraded Cellulose Nitrate can be a volatile substance causing damage to other closely stored materials. Correctly identifying this material will help inform the future care of the dress and prevent deterioration to an already vulnerable silk object.

Magnification of zip slider Advert from 1935 for ‘Lightning’ zips

Magnification of zip slider Advert from 1935 for ‘Lightning’ zips

Image ©Copyright of the University of Glasgow and courtesy of Manchester City Galleries.

I am currently just over half way through the conservation of the dress which has mainly involved applying stitched support patches to the damaged areas. I hope to complete my treatment soon and return it to its former glory when it can be safely mounted on a mannequin for display.