by Aisling Macken, 2nd year student, MPhil Textile Conservation.

As part of the MPhil programme at the Centre for Textile Conservation we undertake a work placement at a museum in the summer between our first and second years and it is always thrilling when objects we have conserved during our placements go on display.

During my placement at The British Museum I had a chance to work on some truly fantastic objects, one of my favourites was a South African Ndebele beaded wedding blanket dating from around 1940. The blanket, made of wool with attached panels of glass beadwork, is now on display in the exhibition South Africa: The Art of a Nation.

During the conservation treatment I worked along side Monique Pullan, Senior Conservator, and together we discovered that the blanket, while slightly dirty, was in overall good condition.

The main issue was that the threads used to create the beaded panels were weakening and had already broken at various points creating splits in the beadwork, resulting in loose beads and a distortion of the graphic imagery. Our treatment plan was straight forward: we proposed to surface clean the beads and wool blanket removing dust and dirt, and sew the splits closed, which would secure the loose beads, strengthen the vulnerable areas, and restore the imagery of the graphic designs.

The strengthening of the vulnerable areas became ever more important as we soon discovered that the blanket would have to be displayed just off vertical in order to fit it into the display case. This angle of display is not ideal for a textile of this nature, due to the extreme weight of the beaded panels. (It may not look heavy in the photographs, but it took four people to transfer the blanket onto the studio table for conservation!). While we considered how we would make the blanket strong enough for exhibition, we began to wonder just what the use of the blanket was. It was clearly too heavy to be used for sleeping, and even display as a wall hanging seemed unlikely. Luckily, there was curatorial information available about the blanket on the museum database. Monique and I learned that blankets such as this one were made and used by women of the Ndebele tribe, who would receive a blanket on their wedding and add the colourful beaded panels throughout her life, often to mark important life events. The blanket would then be worn around the shoulders during ceremonial events.

Monique and I became fascinated by the history of these types of blankets, and the meaning of the imagery of the beaded panels. Further research discovered that the buildings on the blanket were images of the homes of the Ndebele people, which they brightly paint in bold geometric patterns, and the small triangles were electric lights! I learned that many Ndebele people did not actually have electricity, but the lights were included as an aspiration. I was completely fascinated by the blanket and looked further into the meaning of the various images.

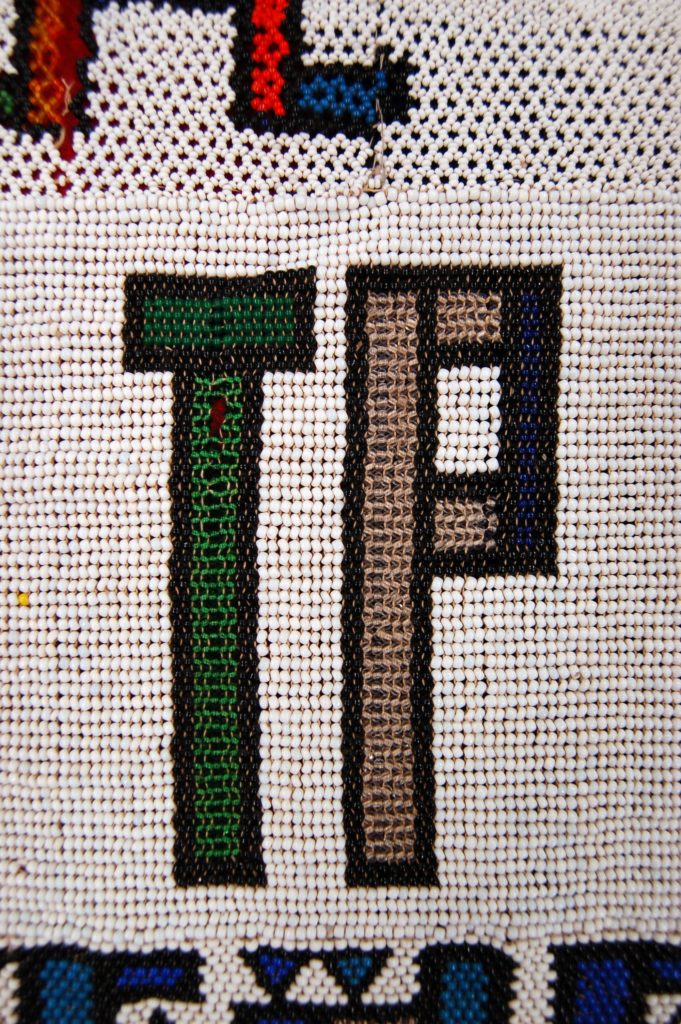

The lettering repeating over the various panels seemed quite curious, as it did not spell any recognisable words, and many of the letters were reversed or appeared to by unfinished or modified versions of letters. Two letters, ‘TP’ repeated three times over the panels, and seemed important to the history of the object. What I discovered is that many of the Ndebele women were illiterate, and took shapes and letters they saw around them from billboards and signs and modified them to be visually appealing design elements. Interestingly, ‘TP’ were the first two letters of the car plates from the Praetoria region of South Africa, where the Ndebele people live. This information gave a fantastic insight into the social history of the blanket, and the women of the Ndebele tribe.

I found that the research of the history of the beaded wedding blanket to be a fascinating part of this conservation treatment. While the treatment was very successful, and the overall look, structure and strength of the blanket is greatly improved, learning about what this particular piece stands for, the aspirations and cultural identity of the Ndebele people, sticks in my mind as one of the most memorable projects during my internship at the British Museum.

Monique and I were filmed during the conservation of the blanket, be sure to watch the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Cuo7x1-Roc

And check out the exhibition South Africa: The Art of a Nation at the British Museum until 26 February 2016.

Bibliography

Priebatsch, Suzanne and Natalie Knight. “Traditional Ndebele Beadwork” in African Arts, vol. 11 no. 2 (1978): 24-27.

Hosford , June and Patricia Davison. “Conserving Ndebele Beadwork” Curator: The Museum Journal, vol. 21 issue. 2 (1988): 85-95.