by Callie Jerman, second year student, MPhil Textile Conservation

It’s strange sometimes how themes can re-occur throughout a project or course. For the current second-year students one theme of the semester was ‘pesticides’.

Historic pesticide use in museums is a huge problem, as a wide variety of toxins were applied to objects, starting in the late 18th century and ending in the 1970s. Often museums and private owners did not keep records of what pesticides were applied and when they did, they were rather startling by today’s standard. The book Taxidermy and Zoological Collecting, published in 1894, describes the following mixture used at the U.S. National Museum:

| Saturated solution of arsenic acid and alcohol | 1 pint. |

| Strong carbolic acid | 25 drops. |

| Strychnine | 20 grains. |

| Alcohol (strong) | 1 quart. |

| Naphtha, crude or refined | 1 pint. |

One would think that any one of those constituent parts would be sufficient to deter pests, let alone all of them mixed together – they certainly were thorough! This poses a problem for museum staff, including conservators, who work in close proximity with these objects because many of those components will still be present 100+ years later. And if your object might contain arsenic, you will probably want to take appropriate precautions!

After in-class discussions and some research, I got some hands-on experience with this problem. My treatment object last semester was a Royal Scots Belgic Shako from the collection of Dumfries Museums. The round felt hat, probably made of a fur felt, has a short leather brim and a distinctive extended front panel. The front is bound in a woven trim, there is a piece of velvet ribbon above the brim and the top of the hat is lined in a black, twill-weave fabric. Sadly, the hat is missing several decorative elements, including its insignia and braided cords but it is still a rare survivor in military history as these hats were only worn by the Royal Scots Guard from 1812 to 1816, before being replaced by a slightly less cumbersome style.

DUMFM:0197.1068

Images of Royal Scots Belgic Shako, taken from the Future Museum, a partnership between institutions in South West Scotland which aims to widen access to and participation with region’s history, museums and galleries.

This was an interesting and unusual project for a textile conservator in a number of ways, but two things were initially of concern. One, it had significant past insect damage but no active insects, which perhaps suggested it had been previously treated. Two, there was a white powdery residue on the front of the hat which was potentially a sign of arsenic trioxide, an effective pesticide that also happens to be poisonous to humans. It was suddenly very important to identify the white deposit in order to determine a safe way to work on the hat.

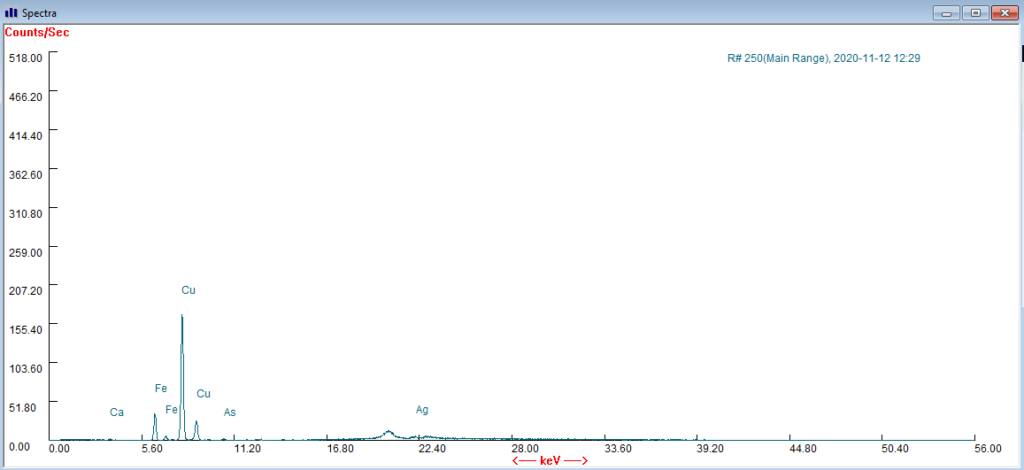

With Dr Margaret Smith, I was able to use a portable XRF (X-ray fluorescence ) gun to run an elemental analysis of the surface of the hat. X-ray fluorescence allows the detection of heavier elements, particularly metals, based on the signature emissions they give off when exposed to X-rays. It is not a technique we use very frequently in textile conservation, but it was really useful in this instance.

Thankfully, while the surface of the hat showed signs of copper, iron, and calcium, the arsenic signal was minimal (and comparable to a test spectra of the air in Glasgow). Although it didn’t resolve the origins of the white deposits, this meant that I was able to move ahead with my treatment without extensive PPE which was reassuring. But we are all now much more aware of the possibility of pesticide contamination than we were six months ago!

Examining and surface cleaning the hat @ University of Glasgow, 2021.

Taxidermy and Zoological Collecting is available through Project Gutenberg, if you are interested in reading more.