by Caterina Celada Prior. MPhil Textile Conservation, student graduate 2020.

In January 2020, I started working on the conservation of what would be my final project of the programme. This was a beautifully embroidered panel in the Arts & Crafts style attributed in design and execution (c. 1880-1905) to Maggie Hamilton. This painter and embroiderer artist[1] who was much involved in the Scottish Arts & Crafts movement with close connections with the “Glasgow Boys” (Glasgow School of Art),[2] also exhibited in the International Exhibition in Glasgow in 1901. Ms Hamilton, whose portrait painted by James Guthrie is displayed at the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow (Inv.Num2907), lived at The Long Croft in Helensburgh. Some of her embroidered works, in the form of decorative panels, can still be admired there.

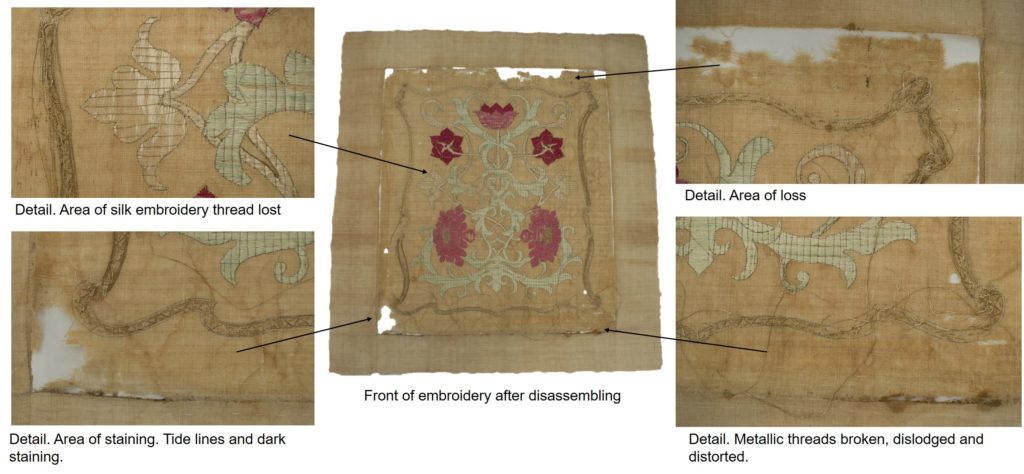

The embroidery, made with silk floss and couched Japanese ‘metallic’ threads[3] (i.e. gilt paper wrapped around silk core), was mounted on a cardboard panel and laced at the back. It was in very poor condition. It is rare to find isolated causes of deterioration in textiles as generally a synergistic interaction of physical and chemical factors occur. In this case, the deterioration pattern of the embroidery suggested the interaction between environmental and intrinsic constructive factors.

Over the years, light damage, the tension caused by the lacing at the back plus the abrasion caused during handling caused extensive damage to both the support fabric and the embroidery threads, which were mostly broken and partially lost.

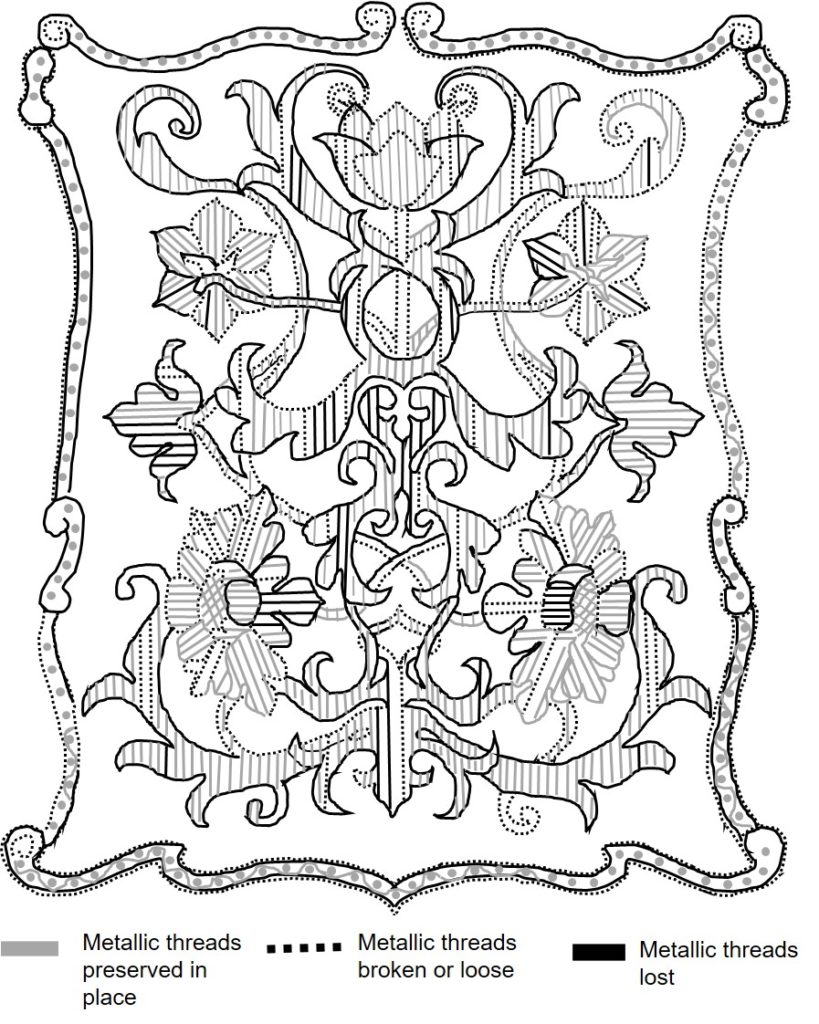

Figure 2. Structural Condition of the Embroidery’s Metallic Threads. © Caterina Celada Prior, 2020.

The structural damage together with the presence of yellowing and tidelines on the ground fabric – caused by the cellulose degradation by-products present in the linen fibres and humidity condensation,[4] were seriously compromising the design and stability of the embroidery.

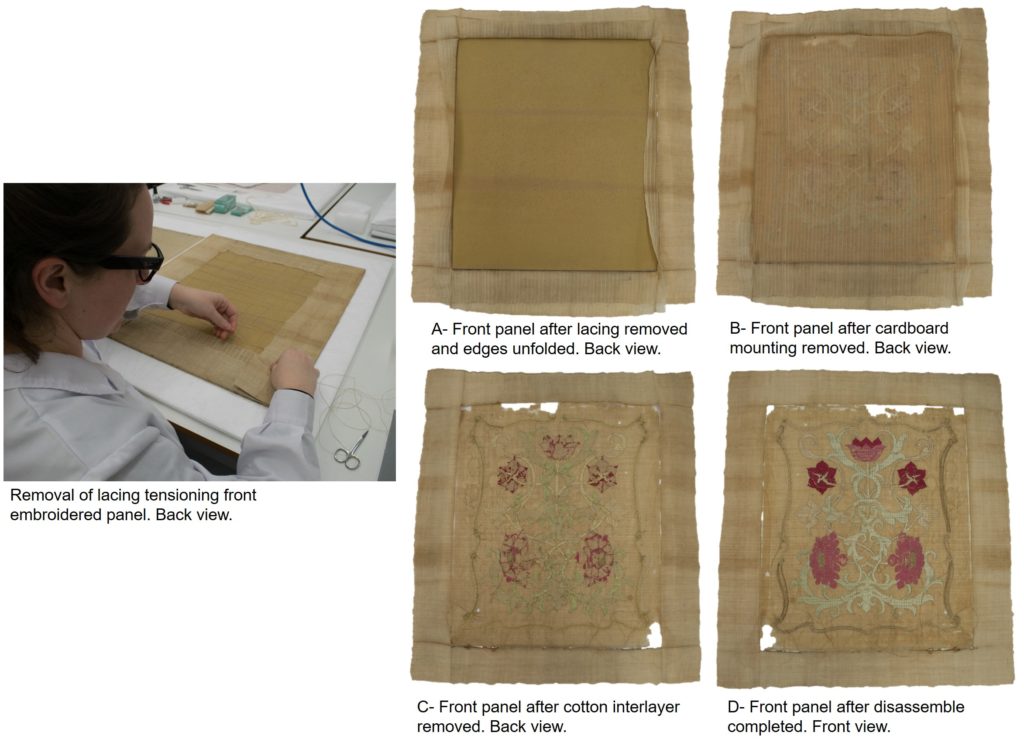

The conservation treatment required thorough evaluation and discussion of the ethical implications involved in the best treatment approach. The embroidery needed to be cleaned, stabilised and supported. Preserving the artefact as a whole, maintaining the panel and existing mount and undertaking the treatment in-situ, was carefully considered. However, prioritising the conservation of the embroidered panel was chosen as the most appropriate approach in this case. Taking into consideration that the internal cardboard mount and the tension caused by the lacing at the back were two of the deterioration causes of the embroidery and that both the cleaning and stabilisation treatments were likely to be compromised by being carried out ‘in situ’, the disassembly of the object was deemed necessary.

Figure 3. First stage of disassembling the artefact. Unstitching perimeter. © University of Glasgow and with kind permission of the client, 2020.

Figure 4. Disassembling. Separation of layers composing the artefact

© University of Glasgow and with kind permission of the client, 2020.

The disassembling provided access to both the front and the back revealing the condition of this embroidery as beautiful as it was fragile. The lack of wash fastness and cohesiveness of the embroidery threads and their gilded paper structure, required alternative methods to wet cleaning by immersion. After mechanical cleaning, a contact wet cleaning method[5] was developed, by locally applying deionised water and blotting out solubilised cellulose degradation (i.e. yellowing) by-products (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Contact wet cleaning with localised application of deionised water and blotting action

© University of Glasgow and with kind permission of the client, 2020.

This was a slow process but the patience invested paid off, providing a noticeable reduction of the staining and slowing down further degradation of the fibres.

After cleaning, one of the most labour intensive and essential parts of the treatment was the stabilisation and support of the embroidery threads and ground fabric. This was achieved by applying a full support of fabric dyed to colour match the ground linen fabric – which revealed how difficult it can sometimes be to achieve a ‘simple’ beige hue! The fabric provides a supportive structure and a visual infill of the areas of loss by visually blending in with the ground fabric (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Artefact before and after structural stabilisation

© University of Glasgow and with kind permission of the client, 2020.

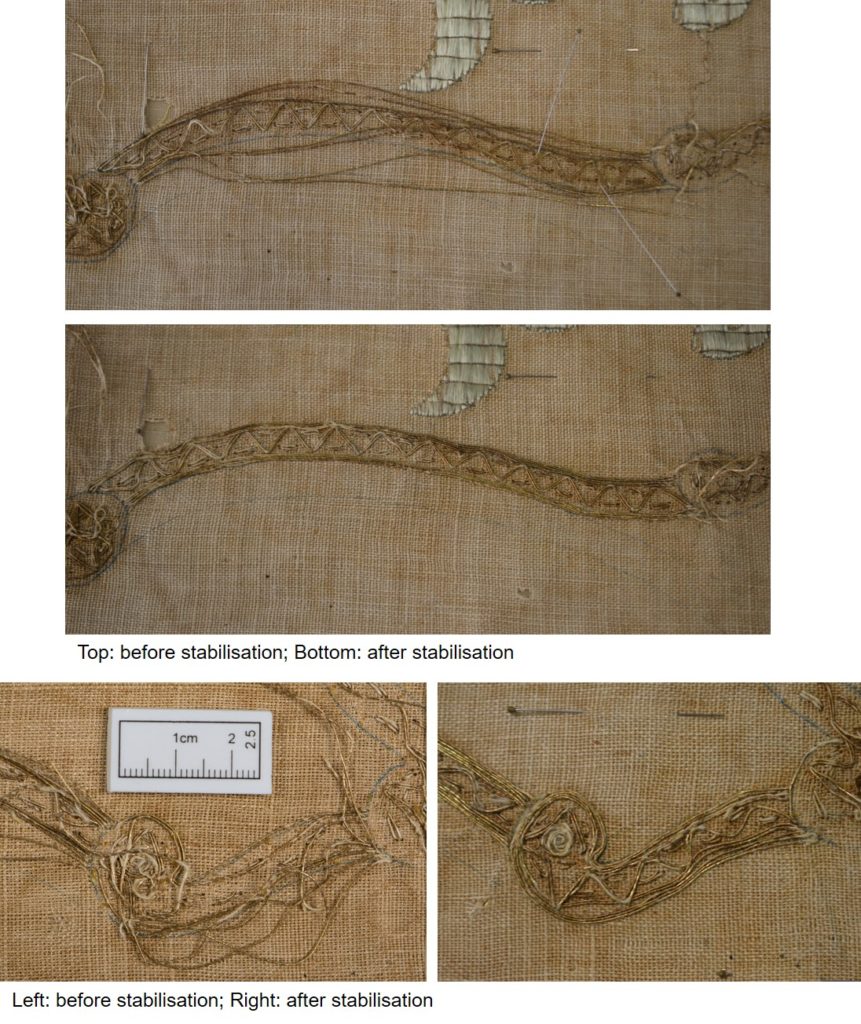

In order to stabilise the distorted and loose embroidered threads, all the metallic threads were relocated and couched down through the ground fabric (Figure 7 & 8) to the new support fabric with brown silk thread, following the original anchoring points and traces of the remaining broken threads. This returned the cohesiveness to the embroidery and the brown silk threads – applied following the pattern of the couched metallic threads, helped in visually completing the missing metallic threads, maintaining at the same time an obvious difference with the original embroidery (Figure 8). As much as it was a labour intensive intervention, securing the entire embroidery following the original stitching pattern made me look at the embroidery with different (more analytical) eyes. Trying to unravel the position of missing and broken threads following the remaining clues, it became a way of connecting with the embroiderer by getting to know the technical process followed and valuing even more the artist’s work.

Figure 7. Stabilisation process of metallic threads

© University of Glasgow and with kind permission of the client, 2020.

Figure 8. Embroidery. metallic threads before and after stabilisation. Details

© University of Glasgow and with kind permission of the client, 2020.

Figure 9. Embroidery. Before and after stabilisation. Details. Left: before treatment; Right: after treatment

© University of Glasgow and with kind permission of the client, 2020.

This project was abruptly stopped in March (due to Covid-19 lockdown). I was able to resume my work in September for few weeks thanks to the support of the Anna Plowden Trust and the Clothworkers’ Foundation Covid Grant Programme. Unfortunately, I was not able to complete the treatment, which is being taken forward this semester by Signe Marie Thøgersen, a second year student.

[1] Alisa Tanner, Glasgow Girls. Women in Art and Design 1880 -1920. Edited by Jude Burkhauser (Edinburgh: Canongate, 1990), 222

[2] Paul Harris & Julian Halsby. The Dictionary of Scottish Painters 1600 to the Present. (Edinburgh: Canongate,1990)

[3] Japanese Thread. Textile Research Centre Leiden. https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/materials/metal-threads/japanese-thread (Accessed April 25, 2020).

[4] Ágnes Tímár- Balázsy and Dinah Eastop, Chemical Principles of Textile Conservation (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998), 25-26.

[5] Rebecca Johnson-Dibb. “Contact Cleaning of Textiles”. 35. 35-37, Textile Specialty Group Postprints. 23rd Annual Meeting, American Institute for Conservation. St. Paul, Minnesota, 1995, 35.